An Excerpt from A Road out of Naknek: Alaskan Salmon Fishing, Long-Distance Running, and Life According to the Tide

~ By Keith Catalano Wilson

Keith Catalano Wilson is an endurance athlete, cross country coach, and commercial fisherman. His regular column appears in Mountain Running Magazine, and his work has been featured in Wanderlust Journal, the Write Launch, and the Young Fishermen’s Almanac. He has both a BS and MA degree in English from Northern Michigan University. He currently lives in Hailey, Idaho with his wife Mandy with whom he founded Wilsons’ Wild Salmon.

An Excerpt from A Road out of Naknek: Alaskan Salmon Fishing, Long-Distance Running, and Life According to the Tide

As summer begins, I start noticing other Bristol Bay fishermen on the flight from Portland to Anchorage. I can tell by the beards, sweatshirts, and a collective musty smell lingering as though these guys have all been on a boat since last summer. I guess they look like me, but I hope I smell better. A good number of them are already wearing their XtraTufs, the rubber boot known as the Alaskan moccasin. Wearing them on the plane leaves room in their luggage, which is usually an empty cooler or plastic tote to carry fish back home in frozen filets after the season is over.

The flight from Anchorage to King Salmon is almost exclusively fishermen. All three towns in the Bristol Bay Borough have airports. Most cities, towns, and villages in Alaska have them, because most of the state is without interconnecting roads. The Bristol Bay Borough School District flies students from South Naknek to King Airfield in Naknek every school day except for when there is inclement weather. The King Salmon Airport, however, is a public, state-owned, commercial airport where Alaska Airlines jets fly in and out during the summer months. The rest of the year, it is only provided with the services of Pen Air.

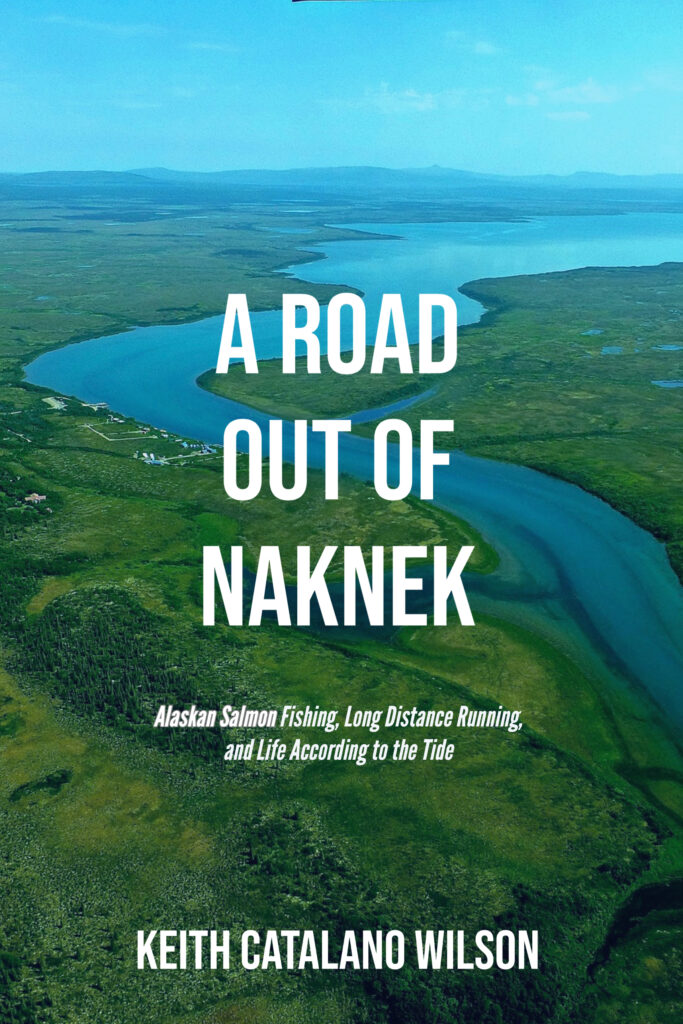

The plane to King Salmon flies southwest, over Cook Inlet, the north edge of the Kenai Peninsula, the Aleutian Range, and Lake Iliamna. I stare out the window at the left wing and a thick, gray shroud below us. We soon dive into the shroud and become enveloped by it until we descend, and it dissipates. Then I see mountains turn to tundra broken only by ponds freckling its endless expanse. The first signs of civilization are houses surrounded by pine trees, alder brush, and birch along the Naknek River, curving and turning where it is still thin and blue near Naknek Lake. The runway is the largest construct made by people. We land fast and hard against it, and I’m home again.

It’s early June, but it’s forty degrees, and it rains on the walk from the plane into the airport terminal, which is crowded shoulder to shoulder with fishermen who wait for luggage. As bags circulate, workers in their orange vests set dozens of identical plastic coolers, totes, and cardboard boxes on the floor. Fishermen flock to them like seagulls flock to a fish on the beach, but there is no pecking order.

Mom and Dad are here. After hugs from both of them, Mom asks me about the trip and Dad is already using his six-foot-four stature to search for my luggage.

“It’s a cooler?” he asks.

“Yeah,” I say. “It’s a red cooler that looks just like every other red cooler.”

Dad smiles. Mom rolls her eyes.

The rest of my luggage is on my back, and when we walk into the parking lot, I throw it into the bed of the truck along with the red cooler full of oranges, grapefruit, watermelon and pineapple — produce with thick enough skin protect it from injuries during travel. The truck is a Dodge Ram, and Dad has had it for years now, but it’s still odd when it’s not the red F-150 of my childhood.

Behind the King Salmon Airport is the Air Force base with its airplane hangars, artillery storage, radar surveillance center, and bowling alley. It’s closed now to civilians, but sometimes I wonder how many bombs, bullets, and bowling balls are still hidden on the premises. Beyond the base, there is a gravel road forking to Rapids Camp, along the Naknek River, and Lake Camp, the entry point of Naknek Lake.

For now, Dad drives us in the opposite direction, over the curve in the road on the bridge over Eskimo Creek. The Alaska Peninsula Highway is about sixteen miles of pavement connecting Naknek and King Salmon — but King Salmon is just an extension of Naknek as far as I’m concerned. It’s on the Naknek River, it’s much closer to Naknek Lake, and it’s powered by the Naknek Electric Association just like Naknek and South Naknek. The official border between towns is somewhere around Paul’s Creek, where Karl told us in kindergarten that his dad had found sunken treasure after wrestling a great white shark. It was while he was scuba diving, he had explained.

We pass Paul’s Creek, and we’re surrounded by what looks like specks of snow on the tundra. It’s cottongrass, and it’s said to signify the numbers of returning salmon. I don’t know who first said it — Yup’ik, Unangan, or white people — but it always seems to be accurate, and it looks like it will be a decent season. The cotton, however, has nothing to do with price. A dollar a pound is a decent amount for sockeye, but I’ve been paid as low as forty cents. Before my time, Dad was paid as much as $2.40.

Homes to our left are spread far apart along the Naknek River, but the right side of the pavement, to the north, is tundra and only tundra until we pass the cemetery. If we were to stop, I would recognize the names carved in stone, where I could reflect on the mysteries of life and death or wonder once again who would want their body overlooking the landfill. I think about how be bury both our dead and our trash and contemplate what it says about us.

After the landfill, Dad drives up a slight incline in the road, and we can see our old house for a moment when bushes aren’t in the way. The house we are headed to now is in downtown Naknek, after the bridge over Leader Creek, and past SeaMar, Icicle Seafoods, Silver Bay Seafoods, Red Salmon Cannery, Cedar Village, Snob Hill, HUDville, City Dock, and Napa Auto Parts. Our house is next to the old Kue Klub, where adults used to play pool. Now it’s surrounded by brush, derelict and abandoned besides the snowshoe hares burrowing beneath it.

Other than fishermen, busy people in Naknek are teachers closing the school year, post office employees sorting boxes, and employees stocking shelves at Naknek Trading, Ace Hardware, or Napa Auto Parts. They’re serving pizzas at D&D or handing six-dollar cans of Budweiser over the bar at Fisherman’s, Hadfield’s, or the Red Dog.

The first week of June is when the canneries come to life, when gates open and windows are uncovered. Cannery workers begin their walk back and forth on the side of the Alaska Peninsula Highway. With all these idle hands, it isn’t uncommon to hear of a vehicle stolen and abandoned in the bushes, a stabbing behind the Red Dog, or a game of Russian roulette gone wrong.

During my first few days back, the clouds are gray, and I am running again by D&D, the restaurant that still holds my definition of a pizza. My diet when I’m not in Naknek consists mostly of whole grains, tubers, vegetables, beans, nuts, seeds, and other items of what my family calls “health food” to optimize running, but I will forever have a weakness for pizza. Anywhere other than D&D, even places in Italy and Greece, I can eat an entire pie by myself before ever feeling satisfaction. I think it’s because I’m trying to relive the generous slather of red sauce, the thick white crust, and the multiple layers of oozing cheese of a D&D pizza of my youth.

As I run by D&D, I take note once again of its wooden sign, painted white with black letters: NAKNEK HOTEL. The rooms are tucked into a corner of the building, and I always wonder who the hell ever stays there, but I know better. There are thousands of people who come to Naknek every summer.

There are many ways that Naknek defies logic. It’s as though it exists in a realm outside of time and space — like the gray shroud the plane descends into is a portal to another dimension. After D&D, I’m on the edge of the Alaska Peninsula Highway, where the pavement ends at Fisherman’s Bar. Maybe I don’t need to run to escape. Maybe I could jump right here, fly into the gray sky above me. I imagine I’d reach the water, or some invisible boundary on the tundra, or I would drift through the clouds and magically appear back on the ground as though it’s some kind of anomaly in space-time. I think again of the pictures of Meteora, the tall rock formations in Greece named for the Greek word for “high in the air.”